In Part 1, I asked why the mortgage mess happened, and why did it happen when it did.

Part 2 explains the role of the Great Moderation and the mild housing cycle in the 2001 recession.

Part 3 explains the role played by securitization of mortgages.

Now I explain how the last recession set in place the triggers for the present mortgage mess.

Let’s

remind ourselves of the strength of the housing market thanks to the Great

Moderation and the mild housing cycle of 2001. If a mortgagee could not make payments, there was no problem for the

mortgage-backed investor. Home

appreciation meant that borrowers could simply sell at a profit if unable to

make payments–or they might refinance and use the cash for another year’s

payments. Or in a worst case, the

mortgage servicer foreclosed, but there was no loss because the house sold for

more than the principal due on the loan.

These

were to two main ingredients of the mortgage mess. Now let’s talk about how they came together in the early 2000s.

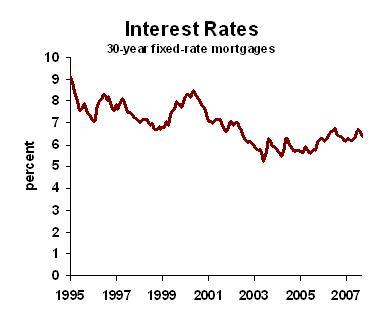

The

recession of 2001 brought interest rates down. The Federal Reserve began cutting short-term interest rates in early

2001, and mortgage rates also fell. Mortgages had been running in the sevens in 1999, then hit eight and a

half percent in 2000. With the recession,

though, demand for credit fell. That,

combined with falling short-term interest rates, brought mortgage rates way

down. By the end of 2002, 30-year fixed

rate mortgages were available at six percent, an interest rate not seen since

1965.

Low

mortgage rates brought first-time homebuyers into the market earlier than

normal. There was also a great deal of

shuffling around of existing home owners, as they moved from one home to

another. Keep in mind that transactions

of existing homeowners just push the peas around on the plate: when a family

buys a new home, it is typically selling an old home, so net demand is

zero. Not so with first-time

homebuyers.

There’s

a normal life-cycle for first-time homebuyers. Young families get their finances in shape, show that they can handle

debt, and accumulate a little bit of down payment. Then they buy. Well,

starting in 2002, first-time homebuyers were able to buy ahead of

schedule. Mortgage rates were so low

that families who had expected to wait until 2004 were able to buy their first

home in 2002. This trend accelerated

when mortgage rates hit their low point, five and a quarter percent, in mid

2003. This interest rate was even lower

than the lowest rates of the 1960s.

So

housing demand was stimulated by low mortgage rates, pushing home prices

up. Builders started to meet the increased

demand, but it took them a while to gear up construction schedules. In the meantime, home prices

accelerated. In the prior decade, the

1990s, home price appreciation had averaged a mere three percent per year. Three percent per year! But low mortgage rates changed all

that. National average price measures

showed six to eight percent gains in the early years of the new century. Those price gains brought out investors.

Stock

prices had peaked in 2002 and fell through 2002. Even after stock prices began to rise, the levels of stock prices

failed to match the earlier peaks, so stock investors were disappointed. They looked around and said, "Gee,

houses sure do well. They never seem to

go down, they just go up." The

three percent gains of the 1990s seem puny by Wall Street standards, but stock

investments are mostly unleveraged; at most, they have a 50 percent loan to

value ratio. Houses can be leveraged,

with 90 percent or even higher loan-to-value ratios. Here’s a bit of arithmetic: if you pay 10 percent down on a house

that appreciates by three percent, your equity grows by 30 percent!

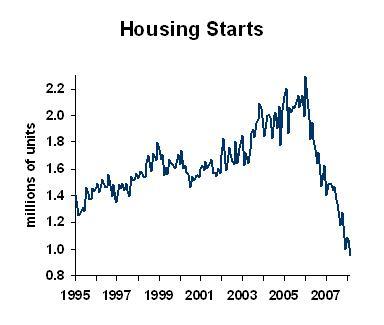

Investors

constituted net new demand, along with first-time homebuyers. In response to the strong demand, prices

appreciated at an even faster rate. Homebuilders

took this as a challenge, and housing starts rose from 1.5 million – a typical

pace – to 2.3 million units, a fifty percent gain.

The

growth of net new demand from first-time buyers and from investors was helped

by carefree attitudes engendered by the Great Moderation, along with mortgage

securitization. Mortgage investors

tested the waters with lower down payments, less documentation of loans,

borrowers with lower credit scores – and the tests looked good. A more conservative sort of person would

have continued the tests through a real downturn, but that sort of person lost

business to the mortgage investors who went full bore ahead.

Our

economic history includes periods of low mortgage rates that did not lead to a

disaster like we are experiencing today. No disaster occurred in those earlier eras because they pre-date the

Great Moderation and mortgage securitization. The 1990s had the critical elements of the crisis, but not the trigger:

low interest rates and a weak stock market.

Everything

came together in the perfect storm that we now call the mortgage crisis.

Given

what we’ve learned so far, what does the future hold for economic cycles,

mortgages and the housing market? We’ll

address that in our final segment.